As in many other places in the world, there is plenty of water in the Netherlands, but not always at the right time. The country has an annual precipitation surplus, but the water that falls in wet periods is often no longer available in times of drought. Sometimes large quantities of fresh water are transported directly to the sea; at other times there is a water shortage in some places. This mismatch between water demand and surplus precipitation as a result of the climate crisis is expected to become more frequent and to increase, not only because of changing weather conditions, but also because glaciers are melting and seawater levels are rising. The circumstances call for alternative ways of thinking and acting: from a naturally wet delta that has to discharge its water as quickly as possible for its inhabitants to survive, to one that retains freshwater and makes it accessible when necessary.

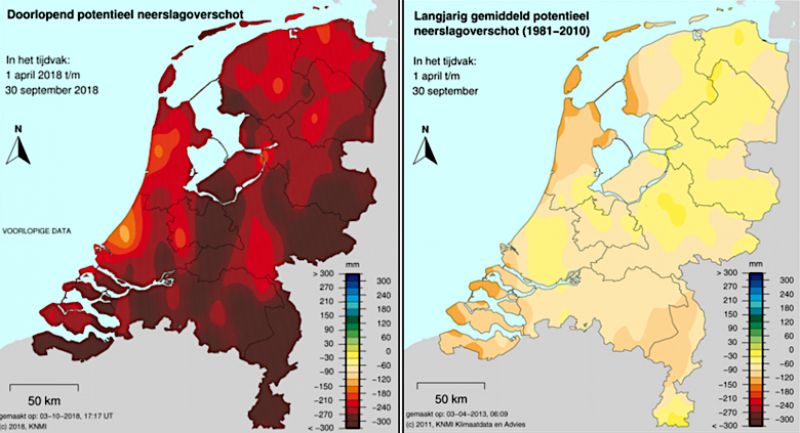

precipitation surplus 2018

source: KNMI

Shortage of Space

Like deltas elsewhere in the world, the Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt Delta is a densely urbanized and economically and ecologically crucial area. That means that space aboveground is scarce, but underground there’s still room, where there have always been major reserves of freshwater, all over the world. This seems to be the most logical place to temporarily store freshwater.

But the subsurface is a vulnerable system that faces its own challenges. In many places in the world, underground freshwater lakes, the aquifers, are under threat, and being drained for irrigation or industrial purposes. This does not happen often in the Netherlands, but the freshwater supply in our delta is also under pressure, mainly as a result of salinization.

In addition, the subsurface is already being intensively used. There are more claims to the space than just that of water storage, for example those of the energy transition and of CO storage. And because of the climate crisis, all of these claims are equally urgent. In the future, claimants will either get in each other's way or will have to share the available space.

All of this is reason for the IABR to investigate the opportunities and frameworks for the large-scale aboveground and underground storage of freshwater. This must be done with an eye for other domains – to see where the various transitions meet and influence each other, but above all to find out where they can help each other. How can the large-scale storage of freshwater act as a lever for the creation of alternative approaches and social added value? How can the underground storage of freshwater contribute to the creation of a resilient delta that can cope with the major transitions that lie ahead?

Connecting the transitions above and below ground

The IABR–Atelier Drought in the Delta will look at all the knowledge that is already available to map out the surface and the subsurface purposefully and as best we can – a precondition for designing there. This will clarify the opportunities and possibilities for the large-scale aboveground and underground storage of freshwater and explain how and where this affects other transitions and their space claims to begin with and, next, show how transitions underground are fundamentally linked to major transitions aboveground, such as the energy transition, food production and ongoing urbanization.

The IABR–Atelier Drought in the Delta is a study by the IABR that is being conducted by Studio Marco Vermeulen under the direction of Marco Vermeulen.